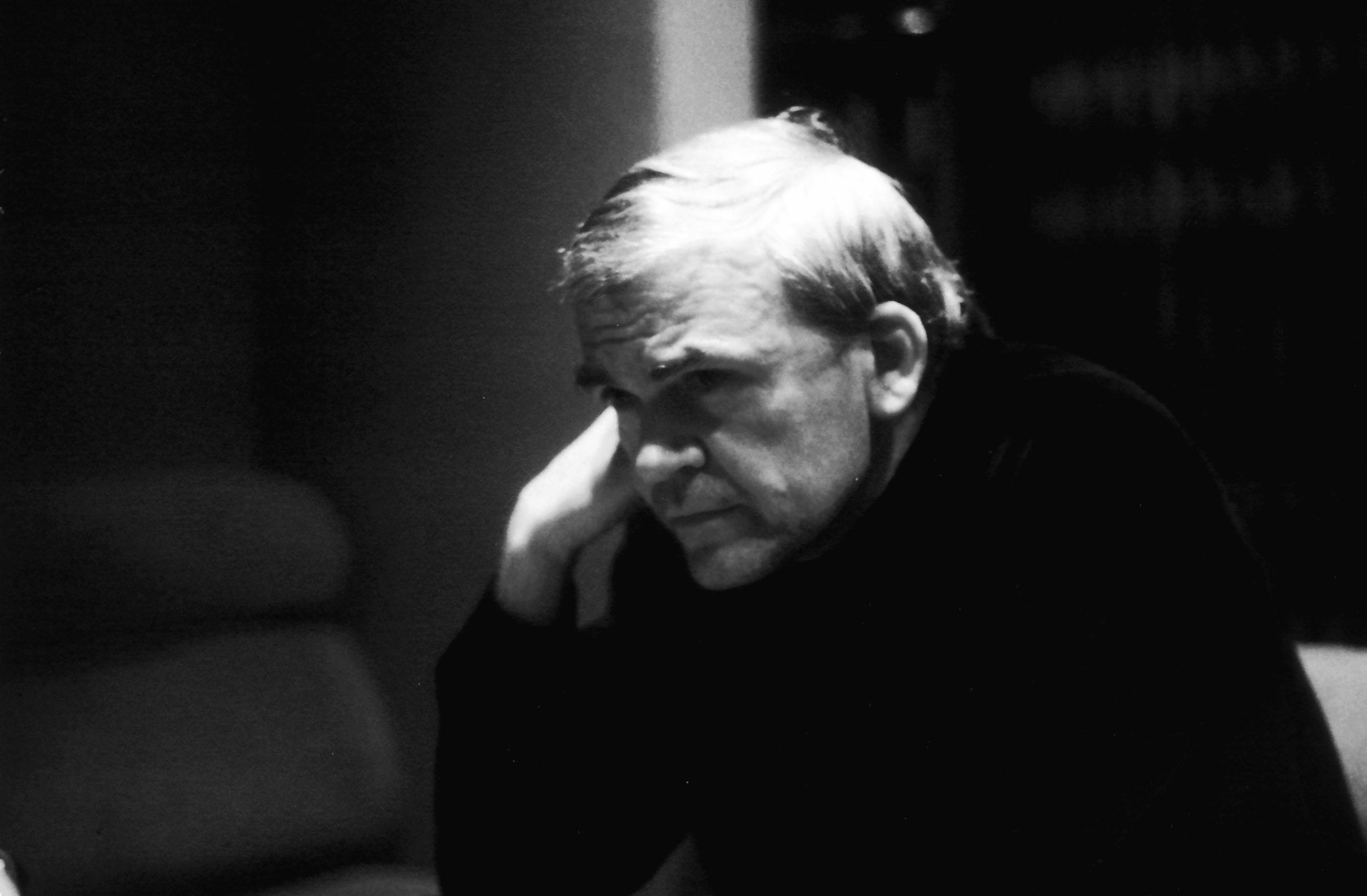

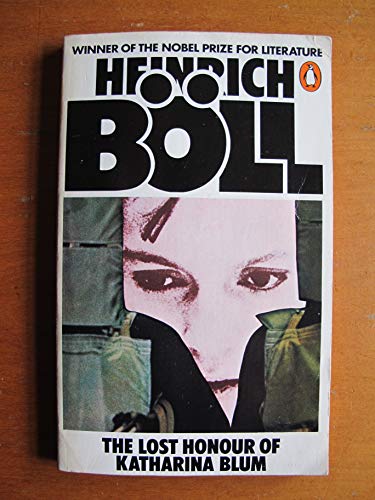

We have traveled far and wide this semester, but our sixth novel presents us with a situation we haven't previously encountered: a country that no longer exists. Indeed, the Czechoslovakia that serves as the setting for Milan Kundera's best-known novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) has been replaced by the Czech Republic, and by the time of the book's publication, Kundera had moved on as well — he left his homeland in 1975 and lost his citizenship in 1979, eventually becoming a French citizen two years later. Arguably, one could consider Kundera a French novelist, since he's spent the past three decades writing exclusively in that language, and the author himself supports this characterization.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being centers around the tumultuous events of 1968 and their aftermath: specifically, the brief hope presented by the democratizing Prague Spring, which was swiftly crushed by a Warsaw Pact invasion (led by the USSR) in August of that year. Tomáš and Tereza are a young married couple: he's a brash womanizing surgeon, while she's still discovering herself both on her own and through their union. Sabina is Tomáš' mistress, and in time becomes a friend to Tereza as well. Through their experience of the revolutionary spirit of the times, Kundera offers us philosophical insights on life and its meaning, from the macrocosm of geopolitical clashes to the ways of individual hearts and minds.

Here's how we'll split up our time with Kundera:The Unbearable Lightness of Being centers around the tumultuous events of 1968 and their aftermath: specifically, the brief hope presented by the democratizing Prague Spring, which was swiftly crushed by a Warsaw Pact invasion (led by the USSR) in August of that year. Tomáš and Tereza are a young married couple: he's a brash womanizing surgeon, while she's still discovering herself both on her own and through their union. Sabina is Tomáš' mistress, and in time becomes a friend to Tereza as well. Through their experience of the revolutionary spirit of the times, Kundera offers us philosophical insights on life and its meaning, from the macrocosm of geopolitical clashes to the ways of individual hearts and minds.

- Fri. October 6: part 1, ch. 1–17; part 2, ch. 1–17

- Mon. October 9: NO CLASS — Fall Reading Days

- Wed. October 11: part 2, ch. 18–29; part 3, ch. 1–11

- Fri. October 13: part 4, ch. 1–29

- Mon. October 16: part 5, ch. 1–23

- Wed. October 18: part 6, ch. 1–29; part 7, ch. 1–7

And here are some additional resources you might find interesting:

- "Four Characters Under Two Tyrannies," E.L. Doctorow's review of the book for The New York Times: [link]

- John Bayley reviews the novel for The London Review of Books: [link]

- John Banville reconsiders the novel for The Guardian 20 years after its release: [link]

- Kundera's "Art of Fiction" interview with The Paris Review takes place just as the novel is gaining international renown: [link]